“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

Alan Henriksen is a fine art photographer based in Smithtown, Long Island, New York. He holds college degrees in Psychology and Computer Science, and is now retired from a long career in software engineering. His award winning photographs have been widely exhibited in national and international shows. Alan’s work has been published in photography magazines, including On Landscape, Black & White, Black+White Photography (UK), Color, and Lenswork, as well as various invitational online galleries, such as LensCulture, All-About Photo, and The Photo-Eye Art Photo Index. Over the years, Alan has developed a style that, in the words of Black & White Magazine Editor Dean Brierly, “… combines acute visual clarity with a highly personal emotional impressionism.” His photographs are held in private and corporate collections. Alan was represented by The Alan Klotz Gallery in New York City from 2012 until the gallery closed in August 2022.

Statement

My interest in photography began in 1958, when my parents gave me a Kodak Brownie camera. Photography was one of my many hobbies until one day in 1964 when I discovered the published work of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams — an event that immediately transformed me into a “serious” photographer. I am fascinated by every step in the making of a photograph: the idiosyncratic and mysterious behavior we call “seeing,” the transformations introduced by the photographic process, and the making of the fine print. Although I have been pursuing my muse for over sixty years, I have yet to stop and ask myself why. The reason has always been intuitively obvious. I am fortunate to have begun photographing at such an early age, since this has enabled me to both preserve and extend the sense of wonder I had as a child.

History

Alan became interested in photography as a hobby in 1958, and began making contact prints in late 1959. His interest became serious in 1964, following a chance discovery of the work of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams at his local library. In 1965 he bought some used photography equipment from a neighbor, including an enlarger and other darkroom essentials, as well as a press camera that included a ground glass for image viewing, allowing it to be used as a view camera.

After graduating from high school in 1966 Alan spent his free time during the summer making photographs, improving both his “seeing” and his technical skills. In September, one of the prints from that summer became the first of his photographs to be accepted and displayed at an international photography exhibition.

In 1967 Alan sent a letter and some photographs to Ansel Adams, care of the newly opened Friends of Photography in Carmel, California. Adams’ generous two-page single-spaced response included a statement regarding work ethic, expressing an idea that has stuck with Alan throughout his career:

“If you were studying to be a musician, or an architect, or a writer you would expect to spend many years perfecting your talent. As so much of the physical aspects of photography is accomplished almost automatically, people often forget the importance of the final 10% or 15% to make a fine print. Without training, deficiencies are hard to recognize. You can develop the hard way, by trial and error, or resolve to study with utmost dedication and seriousness.”

Adams’ letter ended with an expressed desire to follow the progress of Alan’s work, thus beginning a period of mentoring that lasted through 1970, when Alan attended the Ansel Adams Yosemite Photography Workshop.

In 1969 Alan, following the advice of Ansel Adams, purchased a view camera that used 4” x 5” film, along with a few lenses. In the summer of that year he and his wife Mary made their first visit to the Maine coast, starting a photographic project that continues to this day. The majority of his Maine photographs have been made in Acadia National Park and its environs, including the local junk shops.

From 1974 to 1983 Alan was employed as a sensitometrist and software engineer at Agfa-Gevaert’s photo paper manufacturing plant in Shoreham, Long Island. Among the papers coated at the plant was a contact printing paper called Contactone, a paper that was among those once used by Cole Weston to print his father Edward’s negatives. At the same time, Alan began working with a view camera that used 8” x 10” film. He was given permission to take expired Contactone paper home for his personal use, allowing him to further improve his contact printing skills without having to be concerned about the cost of photo paper.

In 1977, Alan took interest in a series of articles written by David Vestal for Popular Photography Magazine. The articles discussed the declining quality of premium photographic papers at that time and what might be done to improve the situation. Alan decided to get involved in the project, and wrote letters to David Vestal, Ansel Adams, and Paul Caponigro, identifying the steeply rising price of silver, and the attendant lowering of silver content in photo papers, as the primary cause of the declining paper quality, and suggesting that Popular Photography publish a reader survey in order to find out whether photographers would be willing to pay a higher price for a higher quality paper. Alan’s letters were received enthusiastically, by letter and phone. Soon he accepted an invitation to be interviewed in New York City by several Popular Photography editors, and began months of correspondence with David Vestal and, occasionally, Ansel Adams. Popular Photography published the poll, written primarily by David Vestal, but with input from Alan, in their June, 1978 issue, and it received a huge response.

In 1978 Alan and his wife built their home in Smithtown, Long Island. This allowed Alan to have, for the first time, a dedicated darkroom, which he built in his basement. The house is still his primary residence.

In late 1988 Alan authored ZoneCalc, an app written for the Radio Shack Pocket PC. The software supported the Ansel Adams Zone System for calculating film exposure and development. It was marketed by the Maine Photographic Resource, and was featured in their catalog. During that same year, Alan and his wife bought a few acres of land in Southwest Harbor, in Downeast Maine, located on Mount Desert Island, home to Acadia National Park. The following year they built a small timber frame house on the property.

In 2005 Alan began using a digital camera for some of his photography. At first he continued to photograph with his film-based cameras as well, but by 2009 his newest camera yielded images whose quality was high enough to allow him to end his film-based photography and work exclusively with digital cameras from then on.

Soon afterwards he discussed this decision with his friend, photographer William Clift, whom he had known since 1977. Bill asked him whether he intended to start making some color photographs, given that digital cameras generally capture their images in color. Alan gave the idea a great deal of thought and soon made up his mind to make a serious attempt at color photography. He then began searching for a suitable subject, one that would provide an opportunity to organize compositions in terms of not only form, value, and texture, but also color relationships. He found his subject upon driving past a junk shop named Super’s Junkin’ Company, in Bar Barbor, Maine. The shop consisted of a large outdoor area plus a number of buildings, displaying all manner of old items for sale, in various states of deterioration. At the time, Alan had been reading “The World Without Us,” by Alan Weisman, a book that describes the various ways in which manmade objects and systems would break down, were mankind to vanish. This idea provided the theme for the series, titled “Living with Entropy,” a project that continues today.

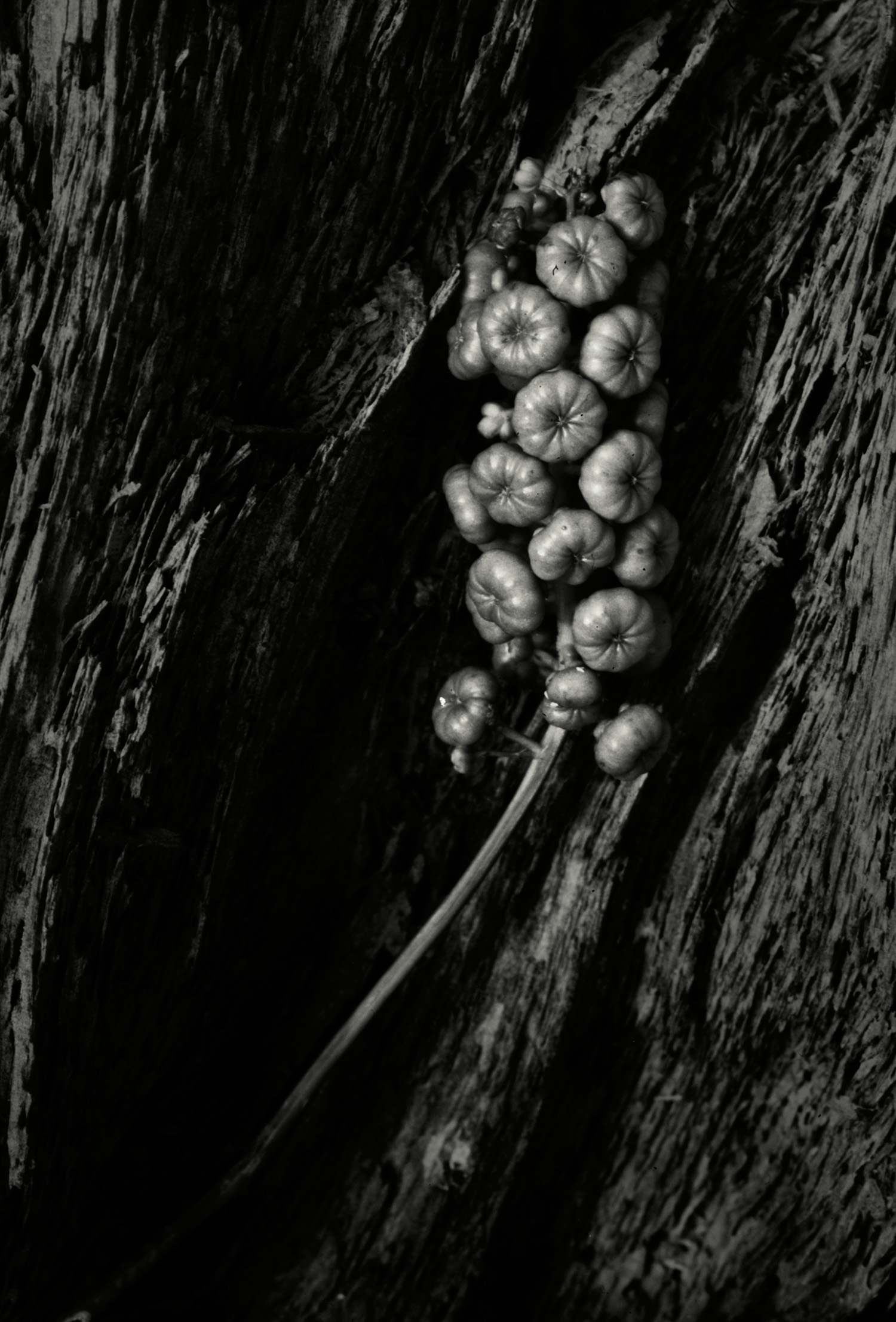

In early 2011 Alan retired from his long career in software engineering, allowing longer and more frequent visits to Maine. He decided early on to attempt to create an entire series of images focused on some, as yet undetermined, aspect of the Maine landscape. During a morning walk with his wife in the Seawall section of Southwest Harbor he discovered a band of seaweed, up to twenty five feet wide in some places, and continuing along the shore for a few hundred feet. Upon making the first few photographs he knew he had found his subject. He went on to make hundreds of photographs of seaweed. The project is still ongoing.

In 2015 Alan’s wife, Mary, died, following over 46 years of marriage. Alan continues to photograph, both on Long Island and in Maine, where he visits several times each year.

“You have integrity and something to say and this world certainly needs all it can get of constructive beauty.”